By Ethan McLeod

October 25, 2018

In January, someone reached out to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive, Hagan’s film-preserving nonprofit, searching for footage of their grandfather, who’d worked at one of the estates of famed literary couple F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. The duo, who lived in Baltimore for five years during the 1930s, were the subjects of the posthumous biographical documentary “Marked for Glory,” produced and screened by WJZ-TV in 1963.

As the inheritor of the station’s archives, MARMIA might have the record somewhere. Hagan knew about the documentary but had never seen it herself, as copies are rare and far-flung. She sent a volunteer in to dig around.

They never did find footage of the requester’s grandfather, Hagan said, but in March, after about 30 minutes of searching, her volunteer did locate a curious, lone canister of nitrate film, an early (not to mention dangerously combustible) medium not in mass use since the 1940s.

“Return to Mrs. Lanahan Scott Fitzgerald,” read a label on the can, an apparent reference to Scott and Zelda’s daughter Frances Scott, known also as “Scottie.” Scottie Fitzgerald’s first husband was named Jack Lanahan. Also inside: a paper referencing B-roll (supplemental footage without sound) scenes, and both Zelda and Scott by name.

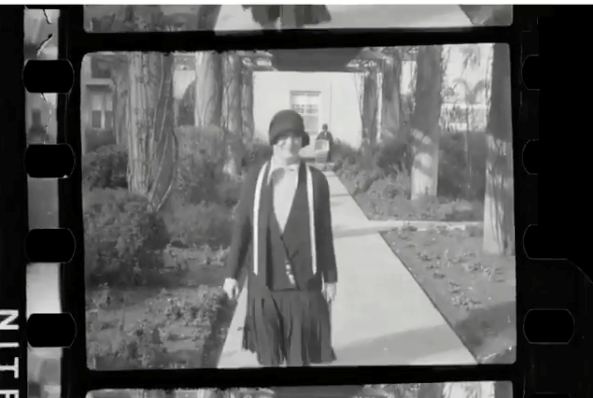

Hagan took the footage to Rockville-based Colorlab to have it digitized. The clips on it are short scenes: a smiling woman strides toward the camera; another flirtingly picks up and strums a ukulele, with palm trees and greenery in the background; a pair of smartly dressed ladies scold a taxi driver and appear to steal his car (almost certainly staged) in front of two men who’ve just walked out of a nearby building. One of the men flashes a grin at the camera.

Hagan noticed one of the women appearing across multiple clips. Could it be Zelda? she wondered.

“I’ve been poring over photos of her being like, Is that her? There are definitely moments when I’m like, Oh, that could be her, and other moments when I look at a photo like, It could not be.”

If it is, MARMIA’s discovery could be a big find.

“There’s very little footage of Zelda,” said Alaina Doten, historian and curator of the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Zelda’s birthplace of Montgomery, Alabama. Some of the only other known video of her comes from the French Riviera, sitting with Scott at a table, or at the home of their friends, the wealthy expats Gerald and Sara Murphy, the historian said.

After Colorlab and MARMIA recently posted the footage, included below, to Instagram, a friend forwarded it to me–and so began a seemingly endless effort to pin down whether this could really be her. I reached out to what wound up being roughly a half-dozen scholars, along with Scott and Zelda’s granddaughter, to weigh in on the discovery.

The first expert I contacted was hopeful, but dismissive.

“I wish it were [Zelda], but it doesn’t really look like her in the face,” wrote Kirk Curnutt, a professor and chair of the English department at Troy University in Montgomery.

Curnutt put me on an email thread with two other Fitzgerald experts to weigh in. Both were equally dubious, saying the woman’s facial features or physical build discount her from being Zelda.

But just to be certain–few experts are, I found–I reached out to others with expertise on the literary celebrities’ lives. Some were excited upon spotting who they believe to be Zelda as one of the cab “thieves,” or among the two women standing and posing toward the end of the footage. A few even theorized others depicted in the film are gilded Hollywood company during the 1920s.

The enigmatic literary couple’s granddaughter sees it.

“That first clip of a woman walking toward the camera certainly looks like Zelda,” Eleanor Lanahan, a filmmaker, artist and writer living in Vermont, wrote in an email. “And Zelda did have slender ankles. I even recognize her rosebud mouth.”

She pointed also to the last clip showing two women, one wearing a striped blouse and holding a hat. Zelda’s seen with the same two articles in this 1927 photo of her, Scott and others in Hollywood, Lanahan noted.

“She is probably Zelda,” she said, with a caveat: “But it’s impossible to tell.”

Several of the scholars I talked to see traces of Zelda in the cab-commandeering scene. (Lanahan notably does not, making the case that the woman’s nose is too straight and her cheeks too round to be her grandmother).

Park Bucker, professor of English at the University of South Carolina-Sumter, spots “a very strong resemblance.” And the behavior–giddily telling off a cab driver and pretending to steal his car–seems like that of Zelda: “It certainly is the type of thing that she would have done, staging this type of thing.”

“I’ve seen lots of pictures of Zelda, obviously, and that woman could very easily be Zelda,” added Jackson Bryer, professor emeritus at the University of Maryland’s Department of English.

Doten pointed also to the golf dress and beret that the woman is wearing as she climbs in and out of the passenger seat, and in a subsequent clip in which she’s posing. “Zelda was a very avid golfer at that time and competed in golf tournaments,” and the attire makes it “entirely plausible” it’s her, she said.

The Fitzgeralds first visited Europe in 1921, and later moved there for nearly two years from 1924 to 1926, spending much of their time in France. MARMIA’s found footage suggests warmer climes, however, given the palm trees in the background.

Perhaps California?

The edge code on the nitrate film, along with details from Scott’s ledger, hints that this may be a record of the Fitzgeralds visiting Hollywood. The code says the film was manufactured in 1926, and the material was expensive enough at the time that someone would typically use it within a year or two, Hagan said.

Scott wrote in his ledger, which he used in part to catalog people and places he’d visited, that they went to California in January and February of 1927–his first stint attempting screenwriting in Hollywood, which Fitzgerald scholar Anne Margaret Daniel has described as “a fiasco.”

Bucker noted this was the same trip where Scott met actress Lois Moran, who inspired Rosemary Hoyt in his later novel, “Tender is the Night,” and whose relationship with Scott sowed bitter tension in his and Zelda’s marriage. He also met Irving Thalberg, a heralded film producer who co-founded MGM, where Scott went on to work briefly a decade later.

“It’s a really, really important two months,” Bucker said.

The names Scott calls out in the ledger are brag-worthy for Hollywood at the time: Hitchcock; the Barrymores; Richard Barthelmess; Patsy Ruth Miller; Morans; and Lillian Gish and Carmel Myers.

It’s possible that those last two, both famous silent film actresses in the genre’s heyday, made cameos in the found footage. Gish resembles the playful ukulele performer, and Myers the driver in the “stolen” cab.

Bucker noted also that both Zelda and Scott called out to Gish in their co-authored 1934 short story “Show Mr. and Mrs. F to Number—”: “A thoughtful limousine carried us for California hours to be properly moved by the fragility of Lillian Gish, too aspiring for life, clinging vine-like to occultisms.”

Independently of one another, Bryer and Doten ventured the same guess as to the identity of the bespectacled man seen walking out of the house before the cab “theft.”

“The man that they’re saying goodbye to, it almost looks like Louis B. Mayer,” said Bryer, referring to the other co-founder of MGM Studios.

Doten highlighted the resemblance to Mayer, comparing photos with the still. She even speculated that the man walking with him could be Scott himself, albeit with little other detail than this: “You can’t see the man’s face, but it bears a strong resemblance to how he would hold his cigarette up with one hand, and his other hand in his pocket.” (For what it’s worth, Lanahan said she thinks he’s “just a little too stoutly built to be him, unfortunately.”)

“This might be reel from them visiting MGM,” Doten said. “My best guess is this is possibly Hollywood footage.”

Still from footage, courtesy of Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive

Scott and Zelda returned to the East Coast from Hollywood in March of 1927, according to his transcribed ledger. They settled briefly in Delaware, renting a mansion called Ellerslie along the Delaware River, near Wilmington, for two years until they moved abroad once again to Europe.

The pair returned to the States again in 1931, first moving to Montgomery, and thereafter here to Baltimore with their daughter, Scottie, in 1932. Since diagnosed with schizophrenia, Zelda entered into the Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Phipps Psychiatric Clinic. Their first home was in Towson, but it caught fire (rumored to have been started by Zelda) and the Fitzgeralds wound up at 1307 Park Avenue in Bolton Hill. It was there that Scott finished and published “Tender is the Night” to poor reviews, albeit with posthumous success.

Joan Hellman, who taught English and developmental reading at the Community College of Baltimore County for 30 years, specializes in the Fitzgeralds’ “Baltimore years.” Hellman also received the lone copy of WJZ’s documentary on the couple from the station’s former editorial director, the late Gwinn Owens, and had it transferred to videotape. She said she made copies and sent one to Princeton University’s special collection on F. Scott Fitzgerald. She also kept one for herself, and sent one to Owens’ family. I’ve asked if she would allow me to view her copy.

Hagan, who’s tried multiple times to reach the Fitzgerald estate and is now in touch with Lanahan via email, said she hopes the found footage can help MARMIA to eventually recreate the WJZ documentary on film. Right now, the nonprofit only has pieces of “Marked for Glory” in its archives.

“I’m still so curious who took the film,” she told me. “Was it for a news reel? Was it because they’re in Hollywood hanging out with a bunch of filmmakers, maybe they have a bunch of 35 mm hanging around? I still have questions about the purpose of the film.”

Hellman, who’s seen the documentary, is convinced it’s not Zelda in the footage.

“I have seen actual film of Zelda (before her illness) and she did not act like these ladies in my estimation,” Hellman said in an email. Zelda’s build would be “a bit ‘hippy'” at that point compared to the more slender woman shown in the footage, Hellman added, as she would have already had Scottie.

Margaret Galambos, a Fitzgerald Society member and former Johns Hopkins University Press staff member, agrees.

“I would say this is definitely not Zelda,” Galambos wrote. She nodded to the attire that Doten had highlighted, noting the “only resemblance being possible clothing style.” However, the woman is “too perky for Zelda at that time,” and her facial features aren’t a match, she said.

Curnutt, of Troy University, concurred in a follow-up message. “I feel very confident in saying that’s not her,” he wrote to Baltimore Fishbowl. “She had a much more distinctive face than the woman in the passenger seat, even when her face was fuller before she lost so much weight in the early 30s.”

All of the academics who believe it’s Zelda hedged that it’s impossible to know 100 percent so many years later, even if they can see her in the images. Still, Bucker of USC-Sumter points to the documentation that came with the found canister as an assurance. “You can very strongly say that this is probably, certainly from Scottie Fitzgerald’s archives.”

And it’s not always that simple with old images, particularly of Zelda, he noted. “The weird thing about Zelda Fitzgerald, she looks different in every picture. It’s hard to pick her out sometimes.”